Blood Diamonds Are Forever, Sierra Leone's Poor Must Not Be

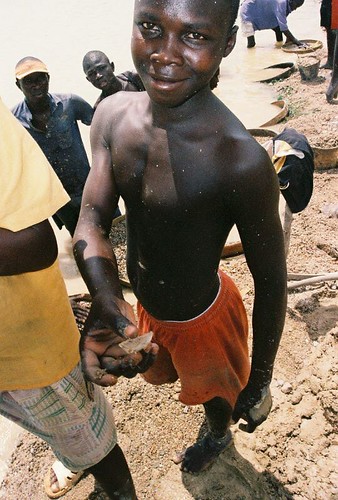

Crossing the bridge to Koidu-Sefadu home to the Sierra Leone blood diamonds I stared at hundreds of people standing knee-deep in the river. I asked Dr. Barrie, What are those people doing? Mining diamonds, the Sierra Leonean doctor responded causally. An imprint immediately laid comparable to textbook pictures of the California gold rush in the 1800s. My first journey to the Kono district capital in the Eastern Region began with a competition to pass a door tied to a 1970s van. As we approached our destination, Dr. Barrie continued, People mine diamonds everywhere here, including their houses. I noted their houses. Underneath a canopy supported by four wooden poles, three women and five children sat silently on one bench and two tires. We passed another. Underneath aluminum sheets tied to the mud bricks of a house foundation, a woman cooked over a wood fire. We have diamonds. We also have gold, bauxite, kayelite, iron-ore, and many other minerals. The people should not suffer like this, said Shabab Sinnah, a Sierra Leonean native from Kono. I knew the statistics and history. They epitomized poverty in resource-rich countries, typically African countries with corrupt governments. In the 2005 Human Development Index, Sierra Leone ranked 176 out of 177 countries, and the devastating war from 1991 to 2002 highlights its recent, dramatic history. Quoted statistics and history lessons did not sufficiently illustrate grave reality. This was the most devastated region in the Revolutionary United Front (RUF) War, Dr. Barrie added. While most follow the diamond trail to Kono, we were following the trail of amputated and war disabled individuals afflicted during the war and abandoned in the post-conflict period. That journey we conducted a national needs assessment of these communities. We sought to understand how and where we could develop a sustainable, replicable model that allows the amputee and war disabled communities to become self-reliant. Along the way, I heard horrific stories and persistent pleas. Ten of us were walking from our village to a safer area of Kono. The rebels discovered and told us, Don t move! We will throw one stone. Whoever it hits will have his or her arm amputated. The rest will be killed. I was hit hard, and the others were shot. My arm was placed on a stump. A rebel started chopping at my arm with a machete, but it was too dull. He asked for another. Afterwards, I fainted as a result of the bleeding, recalls Sabindi, regional chairman of Amputees & War-Wounded Association. The amputee continued, Government has never helped us. When the war ended, we were supported through relief organizations. Examples include Norwegian Refugee Council building us houses, World Food Program giving us rice, and Handicap International providing us with prosthetics. After six months, these organizations disappeared. Since then, we have struggled to live. The dis

Crossing the bridge to Koidu-Sefadu home to the Sierra Leone blood diamonds I stared at hundreds of people standing knee-deep in the river. I asked Dr. Barrie, What are those people doing? Mining diamonds, the Sierra Leonean doctor responded causally. An imprint immediately laid comparable to textbook pictures of the California gold rush in the 1800s. My first journey to the Kono district capital in the Eastern Region began with a competition to pass a door tied to a 1970s van. As we approached our destination, Dr. Barrie continued, People mine diamonds everywhere here, including their houses. I noted their houses. Underneath a canopy supported by four wooden poles, three women and five children sat silently on one bench and two tires. We passed another. Underneath aluminum sheets tied to the mud bricks of a house foundation, a woman cooked over a wood fire. We have diamonds. We also have gold, bauxite, kayelite, iron-ore, and many other minerals. The people should not suffer like this, said Shabab Sinnah, a Sierra Leonean native from Kono. I knew the statistics and history. They epitomized poverty in resource-rich countries, typically African countries with corrupt governments. In the 2005 Human Development Index, Sierra Leone ranked 176 out of 177 countries, and the devastating war from 1991 to 2002 highlights its recent, dramatic history. Quoted statistics and history lessons did not sufficiently illustrate grave reality. This was the most devastated region in the Revolutionary United Front (RUF) War, Dr. Barrie added. While most follow the diamond trail to Kono, we were following the trail of amputated and war disabled individuals afflicted during the war and abandoned in the post-conflict period. That journey we conducted a national needs assessment of these communities. We sought to understand how and where we could develop a sustainable, replicable model that allows the amputee and war disabled communities to become self-reliant. Along the way, I heard horrific stories and persistent pleas. Ten of us were walking from our village to a safer area of Kono. The rebels discovered and told us, Don t move! We will throw one stone. Whoever it hits will have his or her arm amputated. The rest will be killed. I was hit hard, and the others were shot. My arm was placed on a stump. A rebel started chopping at my arm with a machete, but it was too dull. He asked for another. Afterwards, I fainted as a result of the bleeding, recalls Sabindi, regional chairman of Amputees & War-Wounded Association. The amputee continued, Government has never helped us. When the war ended, we were supported through relief organizations. Examples include Norwegian Refugee Council building us houses, World Food Program giving us rice, and Handicap International providing us with prosthetics. After six months, these organizations disappeared. Since then, we have struggled to live. The dis trict chiefs recently gave us 68 acres of land and some seeds. Together we have grown rice on 35 acres, and our first harvest will be next month. We hope that this micro-agriculture project shows others that with more support we can become self-reliant. Koidu-Sefadu has nine amputee and war disabled communities, the most of any area in the Eastern Region. In each community, Dr. Barrie and Shabab asked the same questions in local dialects, What are your most pressing needs? Results from the national needs assessment had the following order (the first three were ubiquitous): Food Security, Child Education, Access to Health Services, Clean Water Supply, Resource Center, and Micro-Credit. In addition to tallying these results, we prioritized the Eastern Region and its largest set of communities, which is in Koidu-Sefadu. On our second journey to Koidu-Sefadu, we initiated our project in reflection of our needs assessment. The district chiefs gifted us two acres of land in a centralized area agreed upon by the amputees and war disabled. We will first build a health center followed by a secondary school that incorporates a technical training and micro-credit institute. Aside from these infrastructural plans, we recently supported the technical cost of the first harvest for their micro-agriculture project. While these services give preferential support to the war disabled and their dependents, the entire community realizes that all benefit. It is encouraging to see fellow countrymen offering their labor services to the war victims for our development project. Awareness of the amputees and war disabled was the initial spark to our development project. Before starting my one-year Global Health Fellowship experience, Issa Toure, a Sierra Leonean native and fellow medical student at Albert Einstein College of Medicine in the Bronx, New York, had told me about the war, its amputated victims, their resettlement to isolated areas, and their medical support from Doctors Without Borders. With hopes of weekend volunteering for the amputees through Doctors Without Borders, I asked a local worker at the medical school to lead me to these communities near Freetown. I arrived at the Hastings community, an hour journey from Freetown. Doctors Without Borders? They helped us during the war and in immediate post-conflict period. That was three years ago, but we still need help, explained Lazarus.

trict chiefs recently gave us 68 acres of land and some seeds. Together we have grown rice on 35 acres, and our first harvest will be next month. We hope that this micro-agriculture project shows others that with more support we can become self-reliant. Koidu-Sefadu has nine amputee and war disabled communities, the most of any area in the Eastern Region. In each community, Dr. Barrie and Shabab asked the same questions in local dialects, What are your most pressing needs? Results from the national needs assessment had the following order (the first three were ubiquitous): Food Security, Child Education, Access to Health Services, Clean Water Supply, Resource Center, and Micro-Credit. In addition to tallying these results, we prioritized the Eastern Region and its largest set of communities, which is in Koidu-Sefadu. On our second journey to Koidu-Sefadu, we initiated our project in reflection of our needs assessment. The district chiefs gifted us two acres of land in a centralized area agreed upon by the amputees and war disabled. We will first build a health center followed by a secondary school that incorporates a technical training and micro-credit institute. Aside from these infrastructural plans, we recently supported the technical cost of the first harvest for their micro-agriculture project. While these services give preferential support to the war disabled and their dependents, the entire community realizes that all benefit. It is encouraging to see fellow countrymen offering their labor services to the war victims for our development project. Awareness of the amputees and war disabled was the initial spark to our development project. Before starting my one-year Global Health Fellowship experience, Issa Toure, a Sierra Leonean native and fellow medical student at Albert Einstein College of Medicine in the Bronx, New York, had told me about the war, its amputated victims, their resettlement to isolated areas, and their medical support from Doctors Without Borders. With hopes of weekend volunteering for the amputees through Doctors Without Borders, I asked a local worker at the medical school to lead me to these communities near Freetown. I arrived at the Hastings community, an hour journey from Freetown. Doctors Without Borders? They helped us during the war and in immediate post-conflict period. That was three years ago, but we still need help, explained Lazarus.  At Hastings, Lazarus was the first amputee that I met. On introduction, I impressionably shook one of his two amputated arms. After successive visits with Dr. Barrie, we validated their urgent pleas for help. Dr. Barrie suggested, If you really want to help them, you need to do it in a sustainable way that supports their self-reliance. You need to start a non-governmental organization [NGO]. After months of meticulous work, Dr. Barrie and I established an NGO in Sierra Leone called NOW (National Organization for WelBody). WelBody means health in Krio, the national language. Starting with nothing is difficult. No one funds a dream, but without funding, the dream remains a dream. I worked with a few friends in the United States to create a non-profit organization called Global Action Foundation (GAF). NOW became the Sierra Leone implementing partner of GAF that is run by its people for its people. Between the efforts of both organizations, GAF and NOW hope to generate funds and implement projects that support the amputee and war disabled communities of Sierra Leone in their vision of self-reliance.

At Hastings, Lazarus was the first amputee that I met. On introduction, I impressionably shook one of his two amputated arms. After successive visits with Dr. Barrie, we validated their urgent pleas for help. Dr. Barrie suggested, If you really want to help them, you need to do it in a sustainable way that supports their self-reliance. You need to start a non-governmental organization [NGO]. After months of meticulous work, Dr. Barrie and I established an NGO in Sierra Leone called NOW (National Organization for WelBody). WelBody means health in Krio, the national language. Starting with nothing is difficult. No one funds a dream, but without funding, the dream remains a dream. I worked with a few friends in the United States to create a non-profit organization called Global Action Foundation (GAF). NOW became the Sierra Leone implementing partner of GAF that is run by its people for its people. Between the efforts of both organizations, GAF and NOW hope to generate funds and implement projects that support the amputee and war disabled communities of Sierra Leone in their vision of self-reliance.

Source: PR Leap